Saccharomyces cerevisiae, baker's or brewer's yeast, are fungi which naturally occur, well, all over the place. Because yeasts are everywhere, it's possible to leave a batter (or grape juice) out and cultivate a new colony of yeast to grow in your food, but this is probably not advisable for most people - especially since yeast (specifically the desirable strain) is commonly available in grocery stores. Although many other strains are generally regarded as safe (S. bayanus and S. pastorianus used extensively in commercial beer and wine making), in cooking and baking, the word yeast refers to S. cerevisiae.

Related Articles

To allow yeast to feast on just wheat flour and water is time consuming, sometimes taking several days to produce enough flavor and volume of small bubbles for delicious, tender bread. Many recipes aid the growth of the yeast by providing a little extra fuel in the form of cane sugar (be careful, an environment too saturated with sugars can shut down yeast activity resulting in a dense loaf) and making sure the temperature is just right to promote yeast activity (around 95°F [35°C]).

The amount of yeast to use, the length of time to allow the yeast to grow, and the balance of other ingredients that may promote or inhibit yeast activity are all unpredictable variables when creating a recipe from scratch. It takes a lot of trial and error to produce a recipe with accurate rise times for a particular amount of yeast (doubling yeast in a recipe won't allow you to halve the rise time) so it's best to start off by sticking with the amounts and times printed in a recipe before experimenting.

Commercial yeast production starts with a small group of healthy yeast organisms that is carefully grown by providing them with nutrients (supplied to them in a slurry called wort). As they multiply via budding (splitting themselves into new yeast cells), the yeast is transferred from test tubes to flasks to tanks. The tanks (called fermentation tanks) start off small and contain a specially formulated wort (usually a mixture of molasses, minerals, and vitamins) enabling the yeast to reproduce quickly and grow (and to be transferred to ever larger fermentation tanks). Fleischmann's has some multi-story tanks that have a capacity of over 60,000 gallons (225,000 L)! When the producer decides it's more cost effective to sell the yeast than to keep multiplying them, they wash and separate the yeast from the wort and other debris and proceed to prepare them for the different types of yeast products.

There are three main types of yeast available to the home cook: fresh, active dry, and instant.

Fresh yeast

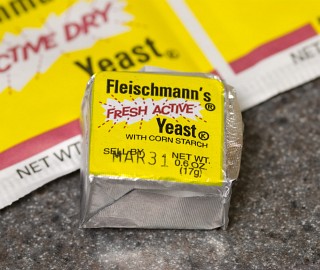

Fresh yeast are live yeast cells mixed with carbohydrates (commonly corn starch) that has been compressed into small square cakes, wrapped, and refrigerated. The yeast is kept cold so it doesn't grow before being incorporated into a recipe and is only viable for about one to two weeks. After that, the yeast runs out of nutrients and dies. Fresh yeast is the most active (that is, gas producing) of the three types of yeast commonly available. According to Fleischmann's Yeast, a 0.6 ounce (17 g) cake of fresh yeast is interchangeable in a recipe to one packet (1/4 ounce or 7 g) of dry yeast. A 2 ounce cake is equivalent to three 1/4-ounce packets of dry yeast.

|

| Close up of fresh yeast (all close up pictures at the same magnification) |

Active Dry Yeast

Introduced in the 1940's, active dry yeast was a major innovation in how people would use yeast and bake breads. To make active dry yeast, live yeast cultures are dried after being removed from the fermentation tanks. A protective layer of yeast debris is allowed to coat the coarse clumps of yeast forming the tiny granules. Active dry yeast is simply dehydrated, dormant yeast cells clumped into grains that await reactivation. To revive the yeast, the grains must be soaked/dissolved in warm water (about 110°F or 43°C is considered optimal) prior to mixing with the dough or batter. Active dry yeast changed the world of baking because it was a shelf stable product that had consistent performance when used. Families on the move and cooks who didn't have constant access to a refrigerator could still use yeast once active dry yeast was made available. (Fleishmann's introduced their active dry product shortly after America entered World War II with the intent of providing yeast to soldiers.)

|

| Close up of active dry yeast |

Instant Yeast

Instant yeast is the name cookbooks give to the third kind of commonly available yeast - but it's almost never sold under that name. Fleishmann's calls their instant yeast product "RapidRise" while Red Star Yeast uses the label "Quick-Rise". With the popularity of bread machines rising, yeast companies are also selling instant yeast as bread machine yeast. In any case, all of these different names mean the same thing - instant yeast. Instant yeast isn't really instant, it's about 50% faster in terms of rise time. To keep things simple, you just use the same amount of yeast as you would active dry, but you don't have to wait as long to get the same rise (which is why recipes typically say something like "allow to rest until volume has doubled, about 1 hour" because we really don't know how long it's going to take because we don't know if you're using the same yeast as we are). Instant yeast is made in a similar manner to active dry, but the drying process has been altered somewhat. According to Red Star, they use a lower heat to produce more porous granules while Harold McGee's On Food and Cooking claims it's a fast drying process. Whatever the process, the end result is that each yeast granule has more surface area and activates faster than active dry. In fact, they activate so quickly, you don't have to soak them in water first - the moisture of the dough or batter will be enough to get the yeast moving again.

When looking at the ingredients of instant yeast, it usually contains sorbitan monostearate and ascorbic acid (an antioxidant used in packaged foods as a preservative; a form of ascorbic acid is commonly known as Vitamin C) as well as yeast. My theory is that to make it a little more "instant", sorbitan monostearate is added as a wetting agent to speed up the absorption of water.

|

| Close up of instant yeast. Granules are smaller than active dry enabling them to moisten faster |

Related Articles

"Although warm rehydration maximizes the performance of instant active dry yeast, companies such as Fleischmann and Red Star suggest that home bakers use water ranging in temperature from 120 to 130, which is excessive. Since, leaching of cell constituents is minimized during rehydration when water is between 70-100 F, using lukewarm to warm water temperature in the dough is advised.

We have communicated with Fleischmann and have been informed that the vast majority of home baking complaints that Fleischmann receives about yeast failures stem from the dough being either too cold, or held at cold proofing temperatures. While 120° F. is certainly excessive for the experienced baker who has control of ingredients, weights, time and temperature, using this temperature does help the inexperienced baker to achieve a faster proof and and to obtain something tangible at the end of the baking process. It is important to note that Fleischmann's recommendations for their experienced retail and commercial customers are dramatically different, and comport with The Artisan's findings."

since i am using a very small quantity of water to rehydrate the yeast and it will be difficult to keep the temperature of the water constant, i find it best to rehydrate the yeast in a small container in a water bath that is kept at 104 degrees for 15 to max 30 minutes. this way, the temp variations will be kept to a minimal

My experience and some others indicates it is just waist of time.

Thanks, Greg

Greg

Proofing yeast achieves different results - speeding up the process. If you need to produce bread faster to meet dinner deadline, proofing may give you advantage.

I do not have any firm statistics on speeding bread-making up by proofing yeast, but have years of making bread without proofing with very good results. For the last 4-5 years I often keep dough in the fridge overnight or during the day for slow rising and like results very much.

Thanks, Greg

Mel

There's a brief thread in the forums here about the no-knead bread. I've been experimenting with the dough for the last couple months with varying levels of success. The technique is more interesting to me in the fact that it produces a flavorful hearth bread without the use of a preferment/sponge. Kneading is usually only a couple minutes of work, while the multiple steps involved in producing a great tasting loaf requires planning and making sure you're in the kitchen to do the next step. The No-Knead method is very hands off. I'll be doing an article on it in the near future.

Proofing yeast achieves different results - speeding up the process. If you need to produce bread faster to meet dinner deadline, proofing may give you advantage.

I do not have any firm statistics on speeding bread-making up by proofing yeast, but have years of making bread without proofing with very good results. For the last 4-5 years I often keep dough in the fridge overnight or during the day for slow rising and like results very much.

Thanks, Greg

greg,

i also have experimented with slow fermentation like you did with intervals of less than a day to three days. i agree with you, from my own experience, 1 day fermentation is better than 2 or 3 days. although, i have heard from people who swears by 3 days fermentation in the refrigerator. i also have experimented with beer yeast and wine yeast. personally, i find beer yeast's fermentation cycle to be much much earlier and stronger (time wise). there was an interesting article about using flor sherry wine yeast for bread to add more flavor. unfortunately red star who makes flor sherry wine yeast discontinued packaging it in small 5 grams packs and i was only able to get some with expiration of dec 2006. the flavor was good but not much rise - could be due to the large amount of dead yeast present. there are other ingredients you can add to the recipe - like diastatic malt powder and asorbic acid (vitamin c). ascorbic acid is used to change the ph slightly ( will not impart an acidic taste like sour dough unless you over added)

personally, regardless of what you do, i will still re-hydrate my yeast to obtain optimal results

george

There's a brief thread in the forums here about the no-knead bread. I've been experimenting with the dough for the last couple months with varying levels of success. The technique is more interesting to me in the fact that it produces a flavorful hearth bread without the use of a preferment/sponge. Kneading is usually only a couple minutes of work, while the multiple steps involved in producing a great tasting loaf requires planning and making sure you're in the kitchen to do the next step. The No-Knead method is very hands off. I'll be doing an article on it in the near future.

Hi michael,

interesting idea and like very much to find out you conclusions. read a little bit about no-knead bread. i think the end result will be small hole and not very elastic bread since the gluten has not been developed through kneading. personally i like chewy bread with big holes and i don't think this will work. i wonder if by varying the gluten percentage you can improve the chewiness even without working the dough. you can purchase pure wheat gluten from health stores and add it to the bread dough to change the gluten percentage.

on a separate subject, i have been trying to make you tial with gluten added bread flour(increased to about 20 percent gluten), salt (1.3%), ammonium carbonate/bicarbonate (don't know which one since it is not specified on the packet)(1.6%), baking soda ((1.6%) alum (1.23% and water (92.9 % hydration). the end products turned out not as puffy like the good ones you get in restaurants. i can increase the puffiness by adding quick rise yeast but the texture and tastes changed slightly. i am wondering if you or your readers know of a good recipe to use. i tried googling it and all the recipes i came across did not work well.

george

That actually isn't true, George, the beauty of the no-knead method is that it produces an artisanal-style bread with a minimum of kneading. The long, slow rise is similar to a gentle knead as it allows the gluten molecules to align with each other, creating the gluten sheets and webs which contribute to elasticity. The wetness of the dough also helps this to happen as the increased moisture helps the gluten molecules to move.

Additionally, the holes in this bread can be huge--just like a ciabatta, a wet dough with minimal kneading time actually produces large holes. I can't remember the scientific explanation off the top of my head, but I can go look it up if you like.

It's a common fallacy to think that more kneading or kneading by hand = better bread, but this isn't necessarily true in all cases.

That actually isn't true, George, the beauty of the no-knead method is that it produces an artisanal-style bread with a minimum of kneading. The long, slow rise is similar to a gentle knead as it allows the gluten molecules to align with each other, creating the gluten sheets and webs which contribute to elasticity. The wetness of the dough also helps this to happen as the increased moisture helps the gluten molecules to move.

Additionally, the holes in this bread can be huge--just like a ciabatta, a wet dough with minimal kneading time actually produces large holes. I can't remember the scientific explanation off the top of my head, but I can go look it up if you like.

It's a common fallacy to think that more kneading or kneading by hand = better bread, but this isn't necessarily true in all cases.

Hi Christine,

After reading you msg, I decided to give no knead a try. You are exactly right and it is quite an eye opener for me!

i have made ciabatta different ways before - direct, biga and poolish. I always thought it is no pain no gain, but this is no pain, same (or maybe even better) gain.

My original thinking of small hole and not chewy was wrong. It produced big holes and chewy bread with a crispy skin on the outside! I will definitely try this method for my naples style pizza dough.

I had to vary Jim Lahey's recipe somewhat due to what is available to me:

used caputo 00 pizza flour instead of all-purpose/bread flour because I have a 50 pound bag and has to use it up.

used all-clad stainless steel dutch oven instead of cast iron/enamal/pyrex since that is all i have. heat retention might be better with cast iron.

sprayed some water mist into the dutch oven right before closing the lid and into the oven. this seems to increase the hole size somewhat.

next project - try using cake yeast and adding a small amount of diastatic malt powder to see if this will improve flavor.

Thanks for posting so I have to verify for myself

George

As for your pizza dough, you may have to tinker with the percentages somewhat--the no-knead dough is so wet that it'll be impossible to work into a round.

Also, if you're working with a domestic oven (even with a tile or other heat-retention device on the botton), use all purpose rather than bread flour--the lower heat of a domestic oven can't handle the higher protein of the bread flour, and bread-flour bases baked in domestic ovens tend to turn out a bit tough on the sides and 'floopy' in the centre. Again, it's another explanation I can't remember but can go look up if you like.

I personally have a table-top pizza oven with a stone floor which gets uber-hot (think 800 or 900F hot), and the pizza it turns out is simply incredible. I've been using Alton Brown's pizza dough recipe from I'm Just Here For More Food as well as the Baking Illustrated one with extra-high protein bread flours (15-17% protein). Delish.

Yes, the recipe is definitely a good one. I already did my 3rd no knead bread and this time I baked it as a ciabatta (double e extra wide slippers)on a pizza stone. i have done conventional ciabattas with kneading, but the amount of knead determines the final product and here you have less variables to deal with.

for naples style pizzas, I will need to change the hydration percentage to around 65 percent, but i don't think this is going to pose a problem. another thing that i might need to change is the yeast percentage (to a lower number) since the room temp fermentation time is so long.

i actually built my own outdoor infrared burner (66,000 btu) pizza oven using refractory bricks with two computer fans under the burners to cool them. the only drawback is that the heat is from the bottom and not from the side and top as in a brick oven. to get around it, i need to heat up the top of the oven first without the pizza stone to get the top hot enough and then heat up the pizza stone. i can get the oven temperature to stabilize around 800 in around 45 minutes and do a 2 min pizza. one of my favorite is a white pizza with re hydrated mission fig, prosciutto and buffalo mozarella (using olive oil to replace tomato sauce).

take care

george

I have developed an Excel spreadsheet, in full working order, stating the actual formula as well as the baker's percentages and the wastage factor that one must consider.

Send me your e-mail address and I will send you a file. It is free as long as you promise to give me your comments on the spreadsheet.

I wil send it as a file, which you then just download.

Regards Reg - (treegro@telkomsa.net)

Why would you get sick? Was the resulting batter/dough not baked?

I used to be able to make dough with yeast dissolved in warm water first and get good results, but yesterday when I used the same process except that I added 3 tablespoonfuls of flaxseed power mixed in the power and let the well-mixed dough sit for hours in the warm room temperature. At the end of the day, the dough refused to rise. It remained dead dough. I hated to throw the dough away and therefore had to make pancakes out of it. It turned out to be good, but I didn't understand why it didn't rise at all.

What went wrong? The flaxseed or dead yeast?

yeast can die / go bad - actually that's one of the benefits of blooming the yeast in warm water - if it bubbles&foams up, you know it is still alive and kicking. no foam, not good to use . . . did you perchance notice?

other oddities - water mix too hot - too hot will kill the yeast.

salt - salt can inhibit yeast - generally not added to the water/yeast directly.

I'm making one for my Biochemistry project.

Not to nitpick, but as this is Cooking for Engineers, a degree of precision seems necessary.

You said:

This is incorrect. Yeasts are fungi. Molds are also fungi. But yeasts are not molds and vice-versa.

Molds grow in multi-cell filament-like structures called hyphae. That is what makes most of them look furry or fuzzy. Yeasts, on the other hand, grow as single cells sort of like bacteria do.

This is incorrect. Yeasts are fungi. Molds are also fungi. But yeasts are not molds and vice-versa.

Molds grow in multi-cell filament-like structures called hyphae. That is what makes most of them look furry or fuzzy. Yeasts, on the other hand, grow as single cells sort of like bacteria do.

You are completely correct! I have no idea what I was thinking when I wrote that sentence... just reading it again was enough for me to go "what? why did I say that?" I've removed the incorrect line from the article. Thanks for letting me know and reducing the errors on CFE!

you might want to elaborate on what you want to do - I'm not sure I correctly understand the question, but some basic points:

fresh pizza dough is most often "stored" in a ball shape; when it is needed it is rolled, shaped, spun in the air, <whatever> into the pan.

the rising of any yeast dough will slow down dramatically when refrigerated. from that perspective, you might not have a "problem" at all - if you're talking about a couple hours, certainly not. overnight,,, the dough will rise noticeably over a 18-24 hour period, even in the fridge.

keep refrigerated, use fairly soon - it does not keep forever - can be frozen.

crumble and dissolve in warm liquid and allow it to bloom / proof before adding to the dough

We are working on a biscuit receipe where we would like to mix the yeast (add to water first?) into the base ingredients, then the biscuits are being extruded via an extruder, dried, and then dry roasted.

Will the yeast cause the biscuits to rise or swell?

small bowl of warm water, should not be so hot you cannot keep your finger in the water for many minutes.

add half a spoon of yeast. stir.

within 10-15 minutes you should see foaming. that shows the yeast is alive and well and producing CO2.

nothing but colored water, it's toast.

dry yeast, kept in the freezer, last several years.

expiration dates presume room temp storage - typically one year.

Quick rising yeasts are a genetically altered mutant form of regular yeast that has been bred to produce lots of CO2 very quickly ... however it also putters out sooner than regular yeast and therefore should not be used for long slow rises in the fridge. Because it is so active, quick rising yeasts also do not require blooming.

The former of these "instant" yeasts is usually only available at a commercial level, although you can find it in some stores or online in 1 pound bags.

I've spent years working on duplicating a recipe that my late grandmother used to make (Italian Easter Bread). What I've done is taken a few different recipes that I found online, merged some of them together, asked my father (who did the shopping for her) what ingredients he used to buy, and use my memory of the taste and aroma to get it close.

My father told me that HIS father used to get fresh yeast from a bakery in that town for that bread. Since the recipes I found called for dry yeast, and since I was not able to find live yeast, I used the packages. I have just found a local bakery (I live on the opposite side of the country from my father) that sells live yeast in 1-lb blocks.

Since the recipe I came up with calls for 3 packages of dry yeast, how much of the live yeast should I use? Do I take that 1-lb block and cut it into a whole bunch of cakes?

http://breaddaily.tripod.com/yeast.htm

many of the larger supermarkets do carry fresh yeast - it's usually in the refrigerated dairy section.

be careful with expiration / shelf life on fresh yeast - it does not hold nearly as long as the dry yeast.

This is to "prove" that the yeast is - alive. If you now see bubbling (CO2) you have "proven" your yeast is alive and you proceed with your recipe.

If no bubbles, you have "proven" that your yeast is - dead from old age or from heatstroke, or is in hibernation from extreme cold.

yeast eats sugar and produces CO2.

This also helps the expression, the exception that "proves" the rule make a little more sense.

Thanks!

This also helps the expression, the exception that "proves" the rule make a little more sense.